A young woman and a young man take turns telling the touching, tearjerking tale of their five-year romance entirely in song--she, backward from bitter end to hopeful beginning; he, the opposite, with the two meeting in the middle for a single duet--for about 90 minutes. It's a simple tale, and, more often than not in the multitude of productions that Jason Robert Brown's The Last Five Years has enjoyed around the world in the 20 years since its premiere, simply told. But such simplicity can also unlock and galvanize the creative imagination in unexpected ways--as it does in most emotional and exhilarating fashion in Out of the Box Theatrics and Holmdel Theatre Company's truly one of a kind and rather game-changing streaming production.

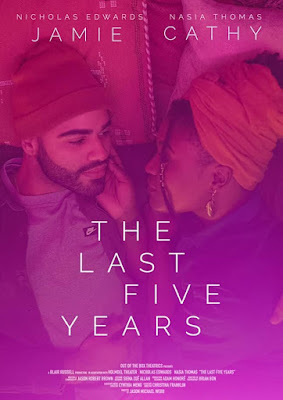

To simply call The Last 5 Years (as it is stylized in the main and end titles) a virtual theater production, while definitely accurate, feels like a bit of a disservice to the visionary work done here by director (and music director) Jason Michael Webb. For one, unlike many streaming theater productions, the love story of ever-striving actress Cathy Hiatt (Nasia Thomas) and wunderkind writer Jamie Wellerstein (Nicholas Edwards) does not play out on a stage in neither a traditional proscenium auditorium nor a black box studio space. Not for nothing is Out of the Box Theatrics named as such; an Off-Broadway company that stages site-specific productions in non-traditional locations such as playgrounds and libraries, that ethos is taken to another, more brilliant level here. All of the action takes place within the confines of a New York City apartment, and beyond proving to be a scene-appropriate setting for nearly all of the show's individual numbers, it's fitting in terms of subject matter in theme. After all, this the story of a life together (or, rather, a stretch of shared life between two individual ones), and witnessing the drama unfold in their living space(s), with many comfortably lived-in details in the rooms and halls from production designer Adam Honoré only adds to the intimacy. But Webb enthusiastically embraces the uniquely creative artifice that comes with live theater when either settings or situations call for it. Wall projections are occasionally but effectively used, not only to evoke other locations but also as organic enhancements, such as making more readily visible a page of a book. And when saying "all" of the action takes place in the apartment, that's no hyperbole: so does the superb work of the six-person orchestra, who appear on camera individually or in various other groupings at numerous points throughout the show. (This recalls one of my favorite live theater experiences ever: an immersive, "multisensory" production of this same show, mounted by After Hours Theatre Company in Los Angeles in 2019, where the orchestra members moved about the shared performance/audience space along with the actors.) Whether seen sitting on a nearby sofa in an opposite corner of a room, strutting right behind one of the actors in an upbeat number, or blending in with the furniture as another passes through a hallway, what sounds on paper like a possible distraction instead helps to replicate for the home audience the irreplaceable electricity of live performance, and the actors are clearly all the more energized by having live musicians also there in the moment instead of just an audio track.

But if Webb's overall staging and design is unapologetically theatrical, his capture of the production is thrillingly and--to be frank--most atypically cinematic. No one would have been surprised, much less offended, if he stuck with the tried-and-true, generally point-and-shoot "aesthetic" adopted by just about all of the pandemic era's streaming theater offerings, from smaller regional productions to even Disney+'s Hamilton. As entertaining and satisfying as a number of those are, they play more as video documents than full-blooded films. As suggested by the movie one-sheet-styled key art, Webb has taken extra care to make his The Last 5 Years also works, in every aspect, as a new adaptation of the material for the screen. While not as extensively as Richard LaGravanese did in his undervalued 2014 feature film adaptation, in some scenes aside from the midpoint duet, Webb has the pair interact, with the non-singing half being a silent observer or participant. In addition to building and thus making more palpable the rapport between the two lovers, in a more practical sense, this choice helps to break Brown's book out of the static, stagey construction of being mostly a series of alternating monologues. Webb and director of photography Brian Bon don't shy away from having the actors directly address the camera as they would an audience in a more traditional stage production of this piece. Early on, though, Webb ably adapts this convention into cinematic terms, in the third song, Cathy's "See I'm Smiling," where Bon's camera becomes Jamie's subjective perspective in the midst of a heated confrontation. That is just one example of the sterling collaboration between Webb and Bon, which also encompasses a nicely balanced juggling between naturalistic lighting and more overtly theatrical flourishes; the creative visual use of organically found aspects of the real apartment space, such as mirrors and other reflective surfaces, and literally built-in frames such as doorways; to the remarkably fluid camera work as Cathy and Jamie travel through the rooms and through the years. Further adding to that visual finesse is the equally elegant work of video editors W. Alan Waters, Rachel Langley, and Becca Nipper. The icing on the cinematic cake is the terrific sound mix; while designed expressly for at-home digital viewing, one can only imagine how Webb's lush arrangements and orchestrations of Brown's still-glorious score would play through an enveloping cinema sound system.

Of course, visual and sound design would only mean so much without the right actors inhabiting Cathy and Jamie, and Thomas and Edwards are more than just right, they're downright spectacular. It goes without saying that neither are conventional choices for the very Jewish writer and his "Shiksa Goddess." But the pair's incredible work here exemplify the powerful benefit in wide-net, inclusive casting (especially in theater, where literalism is generally a secondary concern), and most especially for oft-performed pieces such as this one--not only in how well they do play the roles and sing the songs as written, but in the fresher, unique dimensions they each bring to the characters with their individual performance styles and strengths. Thomas does not fall into the typically lighter, brighter sound of most Cathys, but literally from scene one, her Cathy hits different, with the wrenching opener "Still Hurting" that much more of a gut-punch when the wails of the climax are delivered with her richer, fuller voice. Richer and fuller also aptly describe her performance as a whole. While still vividly depicting the constant insecurities that cripple her and, ultimately, her relationship with Jamie, Thomas's Cathy is not the meek naïf that the character could easily become in less capable hands. Thomas also lends her a vivacious vitality that appropriately builds as the show progresses forward (and Cathy, in turn, progresses backward) and makes Jamie's electric initial attraction to her all the more convincing. Thomas is at her best in the cheeky ode to a stint in summer stock theater, "A Summer in Ohio," which is still the comic showcase/highlight it has always been, but where most lean into the silliness, she instead unearths a sassy sexiness heretofore not associated with the song.

Edwards has somewhat of an even harder job as Jamie, but he is also more than up to the task. Vocally, that's no surprise, for he more than fits the smooth Broadway-pop template of Jamies past. More daunting is the nature of the role itself. By Brown's own admission, this is a semi-autobiographical piece, and his writing can come off as a somewhat overcompensating apology for his relationship failures, with Jamie teetering on being unlikeable and smug by the end. Edwards in no way sugarcoats Jamie's progression from charming, cocksure confidence to outright, outsize cockiness, but never have I seen an actor convey Jamie's inner recognition of and turmoil over his (d)evolution as Edwards does here. His 11-o'clock-number, "Nobody Needs to Know," has always been one of the show's most emotional, but the rawness of Edwards's performance brings it to the level of epic tragedy, that moment where the hero is forced to face in the mirror (literally) the hubris that not only cements his downfall, but that of everyone he claims to love. (Webb's ingenious staging of this song is also the apex of his theatrical and cinematic instincts melding into a higher plane of artfulness.)

That song and scene stings all the more because of the palpable chemistry between Edwards and Thomas, which, as it should, reaches full, bounteous blossom in the only "official" meeting between Cathy and Jamie in the show, the centerpiece duet "The Next Ten Minutes." Marking the couple's engagement and wedding, the measure of this number's success lies not necessarily in evoking the ecstatic joy that should accompany such a blessed event (which, indeed, Webb, Thomas, and Edwards do), but in the foreboding sense of dread knowing that such bliss will eventually, inevitably collapse before long. When Jamie literally disappears as Cathy sings her closing lines of the song, the perfect note of bittersweetness has been achieved--thus ensuring that this groundbreaking production of The Last 5 Years will linger in audience's minds and hearts for far longer than the next ten minutes.

Out of the Box Theatrics's virtual production of The Last 5 Years is now streaming through Sunday, May 9. Tickets are available at the official Out of the Box Theatrics site.

(Special thanks to The Press Room)

The Movie Report wants to attend and cover all your live stage productions! Please send any and all invitations to this address. Thanks!