Even if musical adaptations of films were not an increasingly commonplace presence on Broadway in the last fifteen years or so, the beloved 1990 rom-com Pretty Woman would have been a no-brainer for a tuneful treatment. After all, what is Vivian Ward, Hollywood hooker with a heart of gold whose rich client ends up being the knight in shining designer suit of her dreams, but the one and only R-rated Disney (via Touchstone) Princess? Or to take things even further into the legit theater canon, what is this tale of a rough around the edges young woman who undergoes an external makeover and internal awakening with the help of a privileged male benefactor but a variation on Pygmalion / My Fair Lady? With such familiar archetypes and tropes--and, in this day and age, established/beloved IP's--comes a certain luxury that lends theatrical creatives a certain extra latitude for imagination, what with the audience already having built-in comfort from the tried-and-true source material. But then that very advantage can also, even more easily, lead to a certain creative complacency and even laziness--and that sadly is the case with the squandered potential of the perfectly pleasant but ultimately disposable Pretty Woman: The Musical, which only ultimately underscores what rare alchemy the makers of the now-classic film were able to pull off.

Two of those makers, screenwriter J.F. Lawton and the late director Garry Marshall (in what ended up being his final project), are credited with the book here, and at curtain-up they, along with director Jerry Mitchell and songwriters Bryan Adams and Jim Vallance, appear to inject some freshness into what I would presume is an oft-viewed film for most of the audience members. The opening production number "Welcome to Hollywood" effectively sets the scene of 1990 Hollywood, with its big dreams from little people on the fringes (namely, the homeless and prostitutes), while also showing a smart adaptation note in seemingly establishing the film's bookending "Welcome to Hollywood! What's your dream?" drifter (here played by Kyle Taylor Parker) as a narrator of sorts. But perhaps more importantly to fans of the original film, which, while not being a musical, had a very memorable soundtrack, the song and number also capture the buoyant energy with which Go West's otherwise lyrically-inapplicable "King of Wishful Thinking" kickstarted the movie.

The energy soon dissipates when the book scenes immediately begin soon after, with a lost Edward (Adam Pascal) asking an on-the-job Vivian (Olivia Valli) for directions on a Hollywood street corner. All proceeds about exactly as it does on screen, and that's the issue--one that proves to ultimately plague the production as a whole. There is some validity to the old adage of not fixing what isn't broken (and, in this specific case, has held up remarkably well under the three-decade-plus test of time), but Lawton and Marshall don't so much adapt their work for the screen so much as transplant it directly onto the stage, nearly scene for scene, and even more nearly verbatim. As one of those people who has seen the original film countless times, there admittedly is a certain amount of amusement that comes with anticipating certain lines before they are uttered. But that novelty wears off quickly, leaving one with the increasingly nagging question of why exactly (aside from the obvious financial reason) this production exists in the first place.

That elusive raison d'être theoretically should come from the score, which, unlike the book, is wholly original. However, this is one area where the creative team probably could have more effectively used elements from the film. After that rousing opener, Adams and Vallance eventually find themselves in a losing battle against the lingering impression of the classic movie soundtrack. This is not to say their songs are not pleasant to hear, especially sung by voices as strong as Pascal (who, astonishingly, has lost none of his power, edge, and clarity in the quarter century since his star-making turn in Rent's original cast) and Valli's. Given how the songs here are more or less merely grafted onto the existing screenplay, Adams's well-established brand of agreeable pop is at its best here when called on to catch the general vibe of a scene/beat's movie counterpart, as they do with the opening scene and "Rodeo Drive," a pre-first shopping spree number for Vivian's BFF/mentor Kit De Luca (Jessica Crouch) that reasonably duplicates the raucous, rock-y verve of Natalie Cole's "Wild Women Do." While the commitment to serve up completely original songs is admirable, whenever they attempt to replace the iconic sonic touchstones (no pun intended) from the source, Adams and Vallance are at their least inspired. Vivian's second, and far more fruitful, attempt at a shopping spree makes for a smart intermission break point, and while nothing anyone could ever compose could ever compete with the Roy Orbison evergreen that lent the film its title (which does, eventually, get performed, but only as a half-hearted curtain call), it is a plum opportunity for an all-stops-out act one closer in its own right. Alas, what Adams and Vallance offer is neither melodically nor lyrically memorable from the moment the lights black out, ending the first half with a whimper. Even more meek is their replacement for the film's climactic chart topper, Roxette's "It Must Have Been Love"--a ready-made (both in music and lyrics), barnstorming, no-dry-eye-in-the-house 11 o'clock number if there ever was one. Repeating the word "extraordinary" ad nauseum to a sluggish, soppy tune does not quite pack the needed punch for a moment that calls for a power ballad. (One cannot help but wonder why, unlike other stage adaptors of popular films, Lawton, Marshall, and Mitchell did not simply license and retain the source film's most memorable songs, à la Ghost: The Musical; one can only surmise a veteran pop star like Adams would only agree to compose no less than a 100% original score.)

Hamstrung by the limitations of the book and score, Mitchell mostly does whatever else he can to freshen up the proceedings. Also serving as choreographer, he never passes up an opportunity to showcase the dance skills of his gifted ensemble. While some of these passages are a bit gratuitous, such as an extended dance break for the helpful Regent Beverly Wilshire Hotel manager Barnard Thompson (also played by Parker, in a bit of dual casting that initially seems to have, but ultimately doesn't, have an additional meaning) with one of his bellhops, the impressive moves do help to keep the energy level up. Despite generally lackluster, no more than merely functional, scenic design by David Rockwell (for all of its Hollywood-ized, feel-good gloss, the Marshall film was able to clearly paint a contrast between Vivian and Edward's worlds; not so much here, where the minimalist approach, down to a literally blank backdrop, makes both Hollywood Boulevard and Beverly Hills look rather cheap), Mitchell does craft some interesting set pieces, most notably a recreation of the famous opera scene, where a creative blend of dance, excerpts from La Traviata (immaculately sung by Amma Osei), one of the better Adams/Vallance tunes ("You and I"), and a replica of Julia Roberts's famous red dress make for a highlight that honors but does not completely ape the original. Also working on a similar honoring-but-not-duplicating note is Mitchell's casting, particularly that of the leads, who do make a worthy, valiant effort to step out of their film predecessors' shadows and inject their characters and the pairing with their own unique spins. A suitably dashing Pascal has the easier job, what with Richard Gere being the blankest of slates in the film, and being a generally more vibrant actor, he more clearly tracks Edward's thawing and loosening under Vivian's spell. As such, he and Valli create a beguiling chemistry distinct from the fire-and-ice Roberts/Gere match. Valli makes the most of her first major lead, injecting Vivian with a beautiful and versatile singing voice, loads of charm and spunk, and a bit more of an edge to her presence than America's Sweetheart-era Roberts. She truly is a name to watch.

And that's, ironically, kind of a shame since Pretty Woman: The Musical should, in theory, itself be a star-making vehicle for an actress on the stage as it was for Roberts on the screen. But Valli, as naturally shining a presence as she is, can only do so much with a production where--new, generally forgettable songs notwithstanding--slavish adherence to the film is the general modus operandi. She, or anyone else playing Vivian on stage, can switch up the inflections and rhythms of her line deliveries as much as they want, but that those lines and those costumes are the same as those spoken and donned by Roberts serve as a constant reminder of that iconic turn that was immortalized (and then replayed/rewatched ad nauseum) over 30 years ago, and suffocate any chance for its star--and the show as a whole--from standing on its own.

The First National Tour of Pretty Woman: The Musical is now playing at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood through Sunday, July 3; the production then moves to Orange County at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa from Tuesday, July 5 through Sunday, July 17 before continuing to other cities across America through 2023.

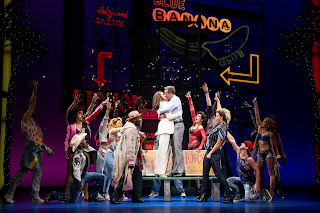

Olivia Valli as Vivian Ward, Adam Pascal as Edward Lewis,

Olivia Valli as Vivian Ward, Adam Pascal as Edward Lewis,and the company of Pretty Woman: The Musical

(photo by Matthew Murphy for MurphyMade)

(Special thanks to Broadway in Hollywood)

The Movie Report wants to attend all your live stage productions! Please send any and all invitations to this address. Thanks!